Part 2 - Distributed Data

Benefits of distributed architectures:

- Scalability

- Fault-tolerance/availability

- Latency

Distributed data architectures may involve:

- Replication

- Partitioning a.k.a. Sharding

Chapter 5: Replication

There are multiple reasons to replicate data, including: scalability, reliability/availability and latency.

The main 3 algorithms to implement replication are:

- Single-leader replication

- Multi-leader replication

- Leaderless replication

Single-leader replication

When only one node - the leader - processes writes. The replicas maintain a copy of the leader’s data to serve read requests only.

Synchronous vs asynchronous replication

100% synchronous replication is not really used. Even if it guarantees consistency with the leader’s data across replicas, the constraints are too restrictive: it takes one replica down to fail the entire system.

Instead, semi-synchronous replication is implemented: only 1 replica is synchronous, not the other ones. If the synchronous replica fails, another one replaces it.

Fully asynchronous replication is widespread, even if there is a risk of data loss.

Failures

Replicated databases make extensive use of log files to handle failures gracefully.

Followers do catch-up recovery. They make a diff between their own log and the leader’s log to fetch the latest data changes since failure.

When a leader fails, the process of promoting a follower to replace the lost leader is called failover. Failover is much more complicated for a bunch of reasons:

- A follower may have data that the new leader does not have. This data may be discarded, but systems may have read it in the meantime.

- Split brain: two nodes think they are the sole leader

- Deciding when the leader is actually down is difficult. What is an appropriate timeout?

Replicating logs

Statement-based replication is not widely used because it can cause a lot of problems, e.g. nondeterministic functions like NOW(), out of sync sequences or side effects… Instead, physical-log-based replication uses the actual log of the storage engine: the WAL for B-tree based engines, or SSTables for LSM-tree based engines. In this case the leader “writes twice” its log: first locally, then sending it over the network to the followers. A big downside: as a low-level object, the WAL is tightly coupled to the storage engine. As a consequence, database version mismatches between nodes are risky. This prevents zero-downtime rolling upgrades. As a middle ground, higher-level logical log objects are often used to avoid coupling replication and storage engines.

Replication lag

Leader-based replication scales when data access is mostly reads, not writes: just add followers. In practice, replication is asynchronous (see above) and brings about eventual consistency and replication lag. Some examples:

Read-your-writes consistency

The problem: first, the user submits data (to the leader, under the hood). Then, the user requests the new data (to a follower, under the hood). Because of lag, the follower serving the user’s data does not have the new data.

There are many ways to provide read-your-writes consistency, i.e. consistency only for the user’s data:

- Identify user’s data specifically and serve it only from the leader

- Serve data from the leader only when the current time is in the interval [last_update, last_update + SOME_TIME]

- Store timestamps on the client’s side to be able to identify lag

Monotonic reads

The problem: the user reads data from a replica, then again from another replica with greater lag. The user sees older data e.g. deleted records. This can be addressed by always routing the same user’s queries to the same replica. This guarantee, weaker than strong consistency, is called monotonic reads.

Prefix reads

Another type of consistency that preserves the order of writes. The problem of returning records in a shuffled order is particularly common in partitioned/sharded databases.

Monotonic reads vs Prefix reads

Monotonic Reads: Focuses on one client’s sequential reads. Ensure there is no going backwards for a given item.

Consistent Prefix Reads: Focuses on global write order. Ensure there is no newer writes without earlier ones, even across different keys.

Multi-leader replication

Multi-leader replication is the combination of two things:

- Single-leader replication, replicated \( n \) times

- Each leader is a follower of the other leaders

Multi-leader replication is much harder than single-leader replication and should be avoided whenever possible. The reason for that is write conflicts between leaders. Now, the benefits are latency (e.g. multiple datacenters), reliability and write throughput.

The typical use case is a multi-datacenter setup. Other use cases include multi-device offline applications or real-time collaborative applications, where each device/user is both a leader and a follower (no strict followers).

Write conflicts resolution strategies

Avoidance

One way to avoid conflicts is to map subsets of records to a unique leader, e.g. assigning users to a given datacenter.

Convergence

Converge to a consistent state with more or less risky approaches. An approach prone to data loss is to uniquely identify each record, then elect one of the conflicting pieces of data as the winner: last write wins if the ID is a timestamp, highest UUID, random selection, majority vote by the replicas… A somewhat less dangerous approach is to algorithmically merge the values (e.g. concatenate). The safest but most demanding solution is to keep all conflicting records and delegate conflict resolution (to an application layer, the user or whatever).

Multi-leader replication topologies

- Circular

- Star

- All-to-all

All-to-all topologies are more fault-tolerant, but require more work to guarantee prefix read consistency (i.e. data coming in in the right order).

Leaderless replication

Leaderless replication is not multi-leader replication with only leaders (like one of the examples of multi-leader setups). There is no concept of any leader node replicating data to followers. Instead, write requests are sent altogether to all nodes, either by the client itself or by a coordinator gateway node. Read requests are also sent to all nodes. In case of conflicts, the reader retains the most up-to-date record, e.g. with the highest version number.

Catch-up mechanisms

Read repair

Say the client fetches a record version 2 from replicas A and B, and version 1 from replica C. The client writes back version 2 on replica C.

Anti entropy

A background process regularly scans the nodes for missing data and makes the appropriate writes.

Quorum consistency

Assume the following setup:

- \( n \) replicas

- A write is successful if \( w \) nodes confirm it

- A read is successful if \( r \) nodes confirm it

To ensure up-to-date reads, \( w + r > n \) must hold. To adjust these parameters, consider the application’s needs in terms of writes vs reads, node availability and so on. The condition is necessary, but not sufficient. On page 181, the author enumerates a few ways stale records can be returned despite quorum consistency. Monitoring staleness is encouraged.

Chapter 6: Partitioning i.e. Sharding

Partitioning

How to?

The problem you want to avoid is a skewed partition causing some nodes to be hot spots. But assigning nodes randomly is not really an option since it would take all nodes to be queried for each request. Instead, there are mainly 2 strategies:

- Partitioning by key range (much like an encyclopedia): efficient with range queries, but can lead to hot spots

- Partitioning by key hash: avoids skewed partitions, but does not work for range queries

A compound primary key implements a hybrid approach where the first part of the key is hashed and the second part is used for sorting: e.g. (user_id, update_timestamp).

Secondary indexes for partitioning

Local vs Global secondary indexes: a read/write tradeoff

Local secondary indexes are easier to implement and maintain: each partition has its own secondary index for its data. On the other hand, they are not efficient for reads because they require all partitions to be queried, unless a specific partitioning has been enforced by the user.

A global secondary index is unique for the entire dataset, and is itself partitioned. It is term-partitioned because each key of the index is attributed a partition. The reads are more efficient but the writes are slower and harder to implement, because each write requires the update of the global index, most likely on a separate partition.

Rebalancing

Always map keys -> partitions -> nodes, not keys -> nodes directly. E.g. if node(key) = hash(key) % nodes, then the entire dataset must be shuffled around when adding a new node.

Strategies:

- Fixed number of partitions: partition size ∝ dataset

- Fixed size of partitions: partition count ∝ dataset (dynamic partitioning)

- Fixed number of partitions per node

Routing

Strategies:

- Client knows which node to talk to

- A routing tier acts as partition-aware load balancer

- Any node is a routing tier (round robin)

See diagram on page 215.

Tools like ZooKeeper keeps track of which partition lives on which node.

Chapter 7: Transactions

A transaction is a set of read/write operations grouped as a single logical unit, with several safety guarantees implied.

ACID

Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation and Durability are the safety guarantees generally provided by transactions.

⚠️These terms are overloaded and ambiguous.

Atomicity

Atomicity refers to the following binary property of a single transaction: the group of operations encapsulated by the transaction either succeeds (commit) or fails (rollback, abort) as a whole. There can be no partial failure.

Atomicity is not about:

- Concurrency

- Temporality

- Multiple isolated transactions

The benefits of atomicity include safer retries, easier application error handling and data integrity.

Consistency

ACID’s consistency refers to data consistency, or data invariants. E.g. sum(debits) = sum(credits) in accounting data.

Consistency may rely on atomicity and isolation, but ultimately it concerns instances of transactions, not properties of transactions.

Isolation

Unlike atomicity, isolation is a continuum. Isolation is about multiple concurrent transactions. The academic term is serializability.

A perfectly isolated database system guarantees that running a set of transactions concurrently or serially always yields the same result. Hence, true isolation is called serializable isolation.

If transaction A consists of several writes, then transaction B can only read either all of A’s writes, or none of them.

Durability

Durability is also a continuous property. A durable database ensures data persistence with a high degree of reliability. Durability depends on both hardware (failure rates, quality) and software (file systems, replication strategies). Even external factors, including weather conditions and geographic location, can influence durability.

ACID transactions are multi-object operations

Nowadays, atomicity and isolation are a given for single-object operations on a single node. Atomicity is often implemented with WALs, and isolation relies on locks. So transactions usually do not entail this specific context:

| Single-node | Distributed | |

|---|---|---|

| Single-object operation | X | O |

| Multi-object operation | O | O |

Weak isolation

In practice, most databases do not implement serializable isolation, but weaker forms of isolation for performance reasons.

1 Read Committed

- Only committed data is read

- Only committed data is overwritten

In other words, no dirty reads or dirty writes allowed.

Implementation details

Locks are used to prevent dirty reads or write. Usually, only writes use locks. If a value is locked by an ongoing write transaction, read requests are served the “old value”, i.e. before the ongoing write transaction.

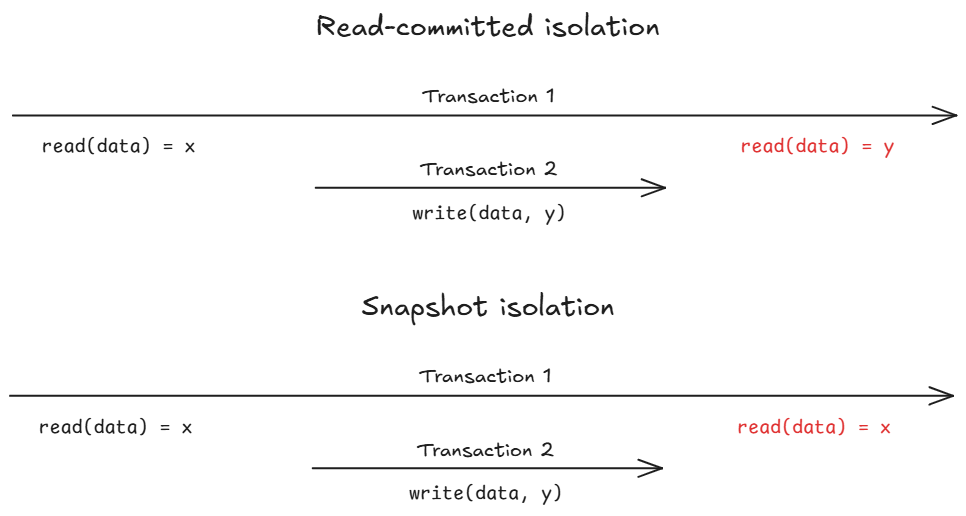

2 Snapshot isolation

This level of isolation guards against nonrepeatable reads:

Implementations details

Much like Read Committed isolation, Snapshot isolation also follows the readers never block writers, and writers never block readers principle: only writes require locks. But now reads rely on Multi Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) to read consistent snapshots of the data at different points in time. For that, an incremental sequence identifies each transaction; whenever data is written, it is also tagged with the transaction’s id.

Other issues and mitigations

In a nutshell, Read Committed isolation ensures only committed data is read/written at runtime, and Snapshot isolation does the same but for data at the start of the transaction. But these weak forms of isolation fail to cover other categories of problems:

| Read Committed isolation | Snapshot isolation | |

|---|---|---|

| Dirty reads | ✅ | ✅ |

| Dirty writes | ✅ | ✅ |

| Repeatable reads | ❌ | ✅ |

| Lost updates | ❌ | ❌ |

| Write skew | ❌ | ❌ |

Lost updates

Updates lost in concurrent read-modify-write cycles:

- Reader 1 and reader 2 read counter C = 42

- Reader 1 increments C: set C = 43

- Reader 2 increments C: set C = 43

- Now C = 43 instead of 44

Solutions:

- Atomic operations: encapsulate the read-modify-write cycle in an atomic operation

- Explicit locking: lock data until completion of the read-modify-write cycle

- Lost update detection

- Compare-and-set: read-modify-read again-write. If the second read is not consistent with the first read, abort update

Note: locking or compare-and-set assume a unique value per data point. This assumption does not hold in replicated database systems. In this case, preventing lost updates rely on atomic operations or conflict resolution.

Write skew

A write skew is a generalized lost update, where the written object can be different from the read object in the read-modify-write cycle.

The read object is typically a set of rows matching a given predicate. At the beginning of transaction 1, this set is \( S_1 \). The write operation is then determined depending on the value of \( S_1 \). But in the meantime, another transaction 2 committed, causing the set to become \( S_2 \). The write operation is then done based on the outdated information in \( S_1 \). \( S_2 \) is called a phantom read.

The only viable solution to guard against write skew is the strongest level of isolation: serializable isolation.

Serializable Isolation

Actual serial execution

To account for the lack of concurrency, in practice the only systems with serializable isolation are:

- In-memory

- OLTP (small transactions)

Example: Redis

Stored Procedures are a way to execute a set of transactions (not the whole database) serially, if the database lives on just one single-threaded node. Partitioning can distribute the system while maintaining serializable isolation, under heavy conditions.

2PL: Two-Phase Locking

2PL breaks Snapshot Isolation’s readers never block writers, and writers never block readers to guarantee serializability.

- Readers must acquire locks in shared mode

- Writes must acquire locks in exclusive mode

Downsides:

- Performance

- Deadlocks

SSI: Serializable Snapshot Isolation

Though not state-of-the-art anymore, SSI has wide adoption (e.g. PostgreSQL) and provides true serializability while maintaining good performance. SSI is an optimistic concurrency control mechanism: instead of blocking transactions upfront with locks, transactions are attempted and committed only if no isolation violations are detected during the process.

For example, SSI will abort a transaction if Write Skew is detected. This is done by identifying an outdated premise: the value read somewhere in the transaction has become stale during execution. There are 2 cases:

- Reads after an uncommitted write: stale MVCC

- Writes after a read

Chapter 8: The Trouble with Distributed Systems

The state of a single node is, for the most part:

- Deterministic: the same operation always produces the same result

- Binary: a process either works or does not work

On the contrary, distributed systems are subject to nondeterministic and partial failures. Distributed computing is about building a reliable system from unreliable components. The chapter lists the usual sources of failure in distributed systems.

- Networks

- Clocks

- Knowledge of the global state by a given node